- Backpackin'

- Posts

- Chapter 7A: Hell on Earth

Chapter 7A: Hell on Earth

Auschwitz.

Hello from Krakow, and welcome to Backpackin'! If you want to join 800 others reading about this weird trip around the world, add your email below:

You can check out my other articles and follow me on Twitter too!

Arbeit Macht Frei. Work Sets You Free. For countless souls, this was their last image of the outside world. For me, it was the first thing I saw when I visited this terrible, horrible place.

My Holocaust History Lesson

Growing up, I knew about the Holocaust, but I didn’t know the Holocaust. It’s fitting that I visited Auschwitz the day after the 20th anniversary of 9/11, because I know 9/11 all too well. Those hijackings shaped the world I grew up in. War in the Middle East. The overhanging threat of terrorism. I have friends and family who lost loved ones that fateful day. 9/11 has always been all too real.

Now contrast that with the Holocaust. I know the dates. The locations. The number of murders. I read a few chapters about it in history classes, and I watched a documentary or two. But it was so long ago, and so far away, that I never really felt it.

Then I read Man’s Search for Meaning. I visited Auschwitz. The Holocaust is the worst catastrophe to ever plague humanity, and it's a shame that it took me this long to fully understand this. Maybe you’re like me. An American who knows about the Holocaust, but doesn’t know the Holocaust. The day to day struggle to survive in the camps. The complete disregard for human life. The vile, sadistic actions of an entire regime.

Our education system teaches us events and statistics, but it ignores stories and struggles. The least I can do to honor the dead is share their experience with others like me. People who know about the Holocaust but don’t know the Holocaust. This is the story of Auschwitz.

Their Story

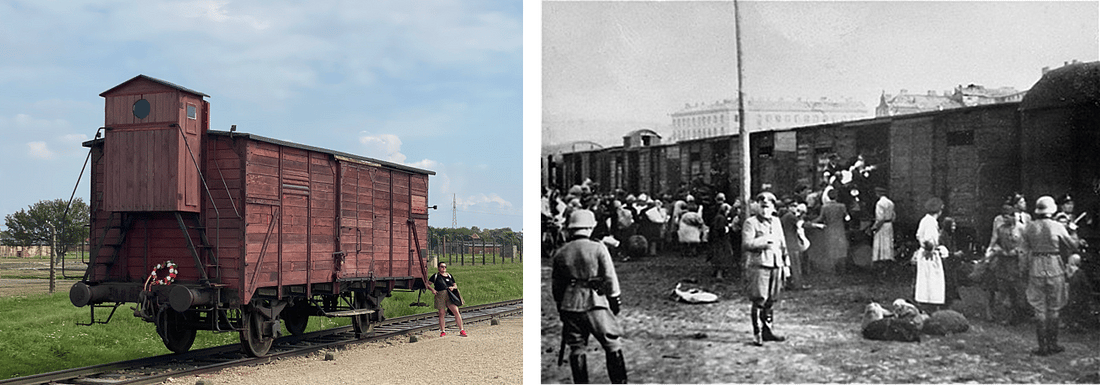

University professors. Housemaids. Auto mechanics. Rabbis. Doctors. Pregnant mothers. Children. It didn’t matter who you were in life. If 3/4 of your grandparents were Jewish, you were arrested, loaded in a train car with one hundred others, and shipped seven days across rail lines to Auschwitz.

With almost no food and water on the journey, the elderly, frail, and infants often died before arriving at their destination. Finally the door opens, and light comes flooding in. You see wooden barracks, stone factories with chimneys, workers in striped outfits, and a German soldier standing 20 feet in front of you.

Soldiers remove the dead from the car while you and the rest of the passengers form a line outside. The soldier in front of you casually points left or right to each passenger, with the majority going left. You are confused, wondering what the significance of these groupings was. Once this process is over, the two groups go their separate ways.

Little did the passengers know, that nonchalant flick of an index finger determined whether or not they would be alive two hours later. See, these concentration camps weren’t meant for imprisonment. In 1941, Nazi leadership convened at the Berlin villa, Wannsee, to discuss the Final Solution to the Jewish question. They viewed the Jews as the final obstacle to a perfect, unified German nation. This solution was mass extermination.

You would either die, or have every ounce of life worked out of you until you wished for death. All Jews would be systematically rounded up and shipped to various concentration camps. All children, pregnant mothers, elderly, and disabled would be killed upon arrival. Think about that. Four year old children with no grasp of the world around them. Expectant mothers eager to hear their babies cry for the first time. Grandparents who wanted to spend their golden years laughing with their grandchildren. These were the people killed with no second thoughts. If you weren’t deemed fit to work when you stepped out of that car, you were killed immediately. Within an hour of entering the camp, 80% of all prisoners were walking corpses.

Here’s the most heinous part of this initial culling: the new arrivals themselves had no idea what was coming next. Tenured prisoners looked on emotionlessly as yet another group of confused camp entrants quietly marched to their deaths. The Jews who were directed left followed a soldier to one of the peculiar chimneyed compounds. As they drew closer, they were overwhelmed by a repulsive smell. Death.

The soldier led the group to a descending staircase, and the prisoners followed these stairs to a lobby of sorts. Here, the prisoners were instructed to neatly remove their clothes and belongings, and store them to the side. After being disinfected, they would have the opportunity to retrieve their things.

That opportunity never came.

The prisoners were then crammed in a shower with the door sealed behind them. When the shower heads opened, a gas known as Zyklon-B, a cyanide compound, began to fill the room. One by one, the prisoners began struggling to breathe. They pounded on the doors. Scratched the walls. Clung to each other as they wept and prayed. Within 20 minutes, 700 innocent souls had perished.

As soon as the gas had dissipated, a small group of prisoners were dispatched by the soldiers to collect any rings, watches, and other jewelry that could later be kept or sold. The women’s hair were cut, as the hair could be sold to create fabrics. Once this scavenging was done, the bodies were shoved into a massive furnace, and their ashes left Auschwitz through the stone chimneys.

Every day. Every week. Every month this march of death was repeated. To the Germans, these Jews weren’t people. They were a scourge to be eliminated. They were the enemy that destroyed Germany’s economy. They were what stood between Germany and world domination.

Maybe those who died on arrival were the lucky ones.

Surviving in Auschwitz came down to a series of decisions. Some decisions made by you. Some decisions made by soldiers. Some decisions made by fate.

The direction of an index finger was the first of many such decisions. The group who stepped to the right may have survived, but many later wished that they hadn’t. They were led to the barracks where they were shaved from head to toe. All of their possessions were either stolen or destroyed. The farmer, engineer, banker, lawyer, and janitor were all the same. Completely naked, with no links to their past lives. Every inmate was given a tattered, insect-filled uniform and a pair of shoes that likely didn’t fit.

Early on, prisoners were photographed with different patches on their uniforms to identify them.

However, photograph costs grew too high as the prisoner count grew, and there had been multiple successful escape attempts. The Nazis began tattooing the prisoners to 1) lower costs and 2) ensure that any escapees could be identified outside of a prison camp. There were no names, no professions, no identities in this hellhole. Just tattooed numbers on your arm.

Six or more prisoners had to share a bunk, and these beds were often made of wet hay instead of sheets. Sleep deprivation was constant, and chronic malnourishment killed more prisoners than everything but the gas chambers themselves. A small bowl of watered down soup and a cup of water were the only things provided to these prisoners.

Some prisoners would be selected to work on labor projects. Building new barracks for future prisoners. Constructing roads, rail lines, and ditches to help the Nazi war effort. These prisoners would dress in their maggot-filled uniforms and poorly fitting shoes before beginning yet another 15 hour day.

Marching 20 miles a day, the feet of many prisoners swelled to the point that they no longer fit in their shoes. They had to carry on barefooted. When winter came, frostbite was rampant across the camp. If you were shoeless, frostbite was inevitable. If your toes suffered from frostbite, they would be amputated. If you could no longer work after the amputation, you were killed.

If you happened to stumble while marching to the work site, you would be beaten to within an inch of your life to teach you “discipline”. If you collapsed under the weight of the iron beams or lumber, or you passed out from exhaustion due to overwork and undernourishment, you were as good as dead once your group returned to camp. If you did everything right, but an SS guard was having a bad day, you would still be subject to his wrath.

The worst part of the mistreatment from guards wasn’t the physical or verbal abuse. It was the complete dehumanization of the prisoners. The guards didn’t talk down to the prisoners as a bully does his victim. They screamed at them as a violent owner does his disobedient dog. The Nazis didn’t view Jews as a subgroup of man, they viewed them as a pestilence. It was a soul crushing existence, and many of the prisoners were completely broken.

Yet even this mistreatment from the guards paled in comparison to the abuse received from fellow prisoners. Kapos, they were called. These Kapos were prisoners that worked with the guards to maintain order within the camps. Guards hand selected Kapos, oftentimes choosing prisoners that were criminals or other outcasts in the outside world. Kapos were given more food, better clothes, and their own rooms in exchange for keeping the other prisoners in check, and they were often more violent than the guards themselves. They would go out of their way to physically beat and verbally berate other prisoners to gain the approval of the guards, as a Kapo who didn’t do his job could be sent back to join the rest of the prisoners. Many prisoners were killed by Kapos themselves.

Maybe the Germans viewed the Jews as inferior. Maybe they abused and murdered prisoners. But to face this wrath from your fellow inmate? Another Jew who was a finger away from marching to the gas chamber with you? One who was given this role by these sadistic soldiers himself? That is treachery in the highest form.

This was life. Day after day. In the freezing cold, you would huddle together with your fellow prisoners to fall asleep. At the break of dawn, you would equip your tattered uniform, lace your hole-filled shoes (if you were lucky enough to have a pair), and solemnly resume your slow march to an inevitable death. At the end of the day, you would receive your small bowl of soup and water, and repeat the process.

As the weeks and months wore on, these prisoners began to look less like humans and more like walking skeletons. You wouldn’t recognize your own reflection, as your body was consuming itself to find any possible source of nourishment. Skin on bones, working 16 hour days. Every step, every breath was a struggle for survival.

I mentioned that survival came down to a chain of decisions. Sometimes, military leaders would decide to “liquidate” entire barracks, labor groups, or prisons. Maybe they needed space for new prisoners. Maybe they needed to relocate soldiers. Whatever the reason, liquidation meant that you were destined for the chamber.

Survival also came down to your relationship with the soldier leading your labor group. Every soldier viewed these Jewish prisoners as sub-human scum, but you stood a chance IF your soldier thought you were useful. If you were a doctor, worked a trade, or provided some sort of utility to your leader, you might last longer than your fellow prisoner. If a soldier learned of an extermination event in the near future, he may move his “favorite” prisoners to a labor team or convoy to another camp. You didn’t know when these events would happen, but your relationship with a guard might be the only thing that kept you alive.

Surviving the day to day prison life was tough enough. Surviving fate was like a game of Russian Roulette. However, instead of only one bullet, the gun was fully loaded as you prayed for a misfire.

Many prisoners lost the will to live. There was an electric fence surrounding the camp, and touching it would kill a man instantly. As time wore on, countless prisoners chose the fence. In the middle of the night, they would run to the fence, finally escaping Auschwitz for good.

Others chose death in a slower way. Occasionally, labor teams would receive small tokens that could be used for additional food. This extra food was paramount for survival, but the tokens could also be exchanged for spare cigarettes traded around the camp. If a prisoner chose to buy a cigarette, his peers knew he would be dead by the end of the week. These men chose a moment of pleasure over survival and continued pain. This was their way of “tapping out”.

Despite the death. Despite the abuse. Despite the omnipresent fight for survival. Some of these prisoners didn’t lose themselves. On the outside, they lost everything. Their family and friends. Possessions. Home. Health. Time. But the hope of something greater, be that family on the outside, religion, or some inner desire stronger than their environment allowed them to overcome it all. They had to compartmentalize all of the horrors around them and focus on the task at hand. They made friends with other prisoners. They prayed to their God. They, in a dark way, even developed a sense of humor in their hellish surroundings. They quietly mocked Kapos that carried themselves highly, and they sarcastically laughed at their rations. They acknowledged that their odds for survival were slim to none, and yet they carried on.

Mankind’s ability to overcome his environment against all odds is incredible, and the prisoners of Auschwitz, both those who survived and perished, are heroes and martyrs alike.

Austrian psychotherapist and Auschwitz survivor Viktor Frankl said, “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how”. This is for the millions who had to find their “why” from the depths of concentration camps around Europe.

My short writing doesn’t scratch the surface on the Holocaust experience. There are so many horrible details not covered, such as Josef Mengele’s experiments on twins and pregnant women. There are other aspects that I didn’t have space to feature, such as survivors’ struggles to reenter a society that had abandoned them, dozens of daring escape attempts, and a million chance encounters that saved prisoners from death. There are so many horrible, incredible, and important stories that I unfortunately don’t have room to tell. Read those stories. Learn about other victims and heroes. Don’t let their lives be lost in vain.

I hope my writing gave at least one person a better understanding of the grotesque suffering that the victims endured. It may seem long ago, but in 2021 we are just as far from the 80s as the 80s are from the Holocaust. This terrible, terrible event is not some distant catastrophe, it was yesterday. And its impact is still being felt around the world today.

That’s all for today. Thank you for reading.

Jack

See below for the previous and next chapter: